This is the third post of a series on Media Ecosystems. The first post draws the outline of the series, while the second post examines the production of mediatisation content through “publishing protocols”.

Media ecosystems

The term ecosystem is primarily used in biology do designate a community of living organisms (plants, animals and microbes) in conjunction with the non-living components of their environment (things like air, water and mineral soil), interacting as a system (Wikipedia). These biotic and abiotic components are regarded as linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Willis (1997) traces back the history of the concept and its adaptation to the description of natural systems. Ecosystems are defined by the network of interactions among organisms, and among organisms and their environment. They can be of any size but usually encompass specific, limited spaces.

By analogy, a business ecosystem applies to a community of economic agents interacting for the balance of all, in a framework favourable to externalities (Teece, 2007).

A business ecosystem finds its roots in the idea of value networks and can be seen as a group of companies, which simultaneously create value by combining their skills and assets. Business ecosystems create value for a participant only when the participant is not capable to of commercializing a product or service relying on its own competences. (Clarysse, Wright, Bruneel, Mahajan, 2014, p.1164)

The concept of ecosystem differs from the one of industry, market or sector, because it relies on the prevalence of external effects. Quite frequently, the externalities come from private or informal information exchanges – on individuals, organizations or institutions – that decrease transaction costs and favour various forms of business clustering. Such kinds of ecosystems could be called “transactional” since most of the externalities come from the impact on transaction costs of circulating knowledge, informal relations and institutional information.

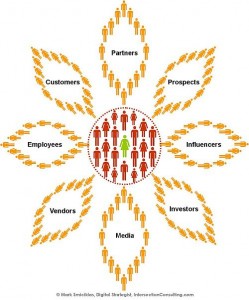

Similarly, one can consider that a communicating society runs like a biotope in which public messages are received and re-emitted by media. Media interaction participates in society coordination although media are not systematically linked together by formal or contractual relations. As such ecosystem contributes to the production of a “favourable notice”, the participants rely on it to commercialize their products. Quite often, “the skills and assets” that are shared by media deal with trademarks or talent names equivalent to “brands” that provide a meaningful context to goods or expressions (Bomsel, 2013). The mediatisation of people, firms or goods proceeds from ecosystems dedicated to specific products. One can distinguish the ecosystem of books, the one of the news, of scientific papers, of plastic arts, of music, of cinema, of sports, etc. But there is also a media ecosystem for fashion, luxury goods, cosmetics, automobile, food, drugs, etc. While transactional ecosystems decrease transaction costs between the participants, media ecosystems produce the public image – the informational complement – of business or institutional agents and their related products.

Digital technologies are bringing new media in all ecosystems: online newspapers and magazines, blogs, science portals, audio and video platforms, social networks… The echoing of the news, for instance, can follow many new routes and reach consumers faster and wider than could the pre-digital media. Moreover, the connection between advertising or mediatising a product and its actual purchase by a customer can be internalised through online procedures: an html link will transform a viewer into a purchaser, an audio or video platform teases for free until the viewer decides to pay for a service. As a consequence, the borders between mediatisation and sales tend to blur. This trend affects the economic means used to internalise the externalities of the media ecosystem. This is particularly sensitive in all the copyright industries that produce expressions to be distributed in a dematerialised form.

The mediatisation of copyrighted expressions

Copyrighted expressions are informational goods that have to be mediatised. An inspired poem or a scientific theorem posted on an anonymous blog will remain unnoticed. The release of a novel, of a scientific article, of a music tune, of a movie or a TV series, of a sports event, follows a symbolic route constituting a publishing protocol. The public image of a movie disclosed at the Festival de Cannes will differ from the one of a blockbuster presented in a Hollywood showy opening, and even more from a B movie released straight on DVD. The mediatisation of copyrighted expressions adds meaning and value to the works. It is achieved through a media ecosystem providing a direct and indirect echo to the works.

Copyrighted expressions differ from other goods by the fact that, being non-rival, they can be mediatised through free consumption. Thanks to external effects, the supply of free copyrighted works can be financed by ads paid by other firms, by authors (gold open access reviews), or by other contents bundled on a publishing platform. Digitization, which extends the non-rivalness thanks to the dematerialisation of the supports, increases the potential of mediatisation through free consumption. Hence, the coexistence of free and pay content – news, music, video, scientific articles, sports, etc. – on the same digital platforms, tends to narrow the gap between mediatisation and distribution.

In effect, a media ecosystem reflects a state of the technology. Let’s take the case of music. Under the phonographic period, music was taped on records and mediatised through record sleeves, radios, concerts, magazines, video clips and record shops. The radios had to notice the release of the records and to start the buzz. Competition between record producers gave even rise to the payola system – a bribe to disc jockeys in order to get aired – that was depicted by Ronald Coase (1979) as a hidden publicity. Concert tours were keeping the topicality of the artists. Magazines were feeding fans with stories related to music performers. At the end of the chain, record shops were the ultimate media displaying the sleeves and their assortment in racks. In this ecosystem, most of the relations between copyright holders and media were internalised by formal arrangements. The production and sales of records was shaping the ecosystem. Broadcasters were paying license fees while getting paid through publicity. Showcase and tour operators were hiring performers as to sell tickets and drinks. For the most popular artists, record producers invested in video clips and TV ads. Distributors were rewarded on record sales. Only a few players (magazines, talk-shows, variety-shows) benefitted from informal cross-externalities.

With digitization, the phonographic ecosystem gets supplemented both on the media and the distribution side. On the media side, streaming platforms and social networks can create and amplify a buzz that was formerly produced by showcases and radios. The online press will link a music review to a playlist that is just one-click from the reader. TV promotion is re-focussed on ads and talent shows whose viewers argue on social networks. On the distribution side, music downloads and, increasingly, streaming services substitute to CD sales.

A key pattern of this trend is the convergence of mediatisation and distribution. Streaming platforms deliver both mediatisation – through free access service and discovery or thematic apps – and distribution. On such platforms, a subscriber can share his playlists with his social network’s friends. Thus, a listener can become a disc jockey, now called a curator, getting followers for his selection service. On video platforms, amateurs can post video parodies that will increase the popularity of the original. Right holders can either accept or refuse such parodies and even, for a commercial use, license performers their music publishing rights. In other words, with the continuous surge and rollout of new media, the music ecosystem gets denser and denser making the internalisation strategies more open and flexible than in the past.

What happens with music also happens with books, scientific articles, news, sports, cinema, TV series… Each copyright industry – characterised by the production and the publishing of specific expressions – is confronted with the surge of new media that change its former ecosystem. For a while, this change has been perceived as a dematerialisation arousing competition or cannibalisation between distribution channels. This view was suggested by the vertical design of the industry resulting from the copyright transaction chain and the distribution of material supports.

Actually, the change is far more sophisticated. The newness of the digital ecosystems is that mediatisation gets blurred with distribution. In other words, digitization makes copyrighted works distribution a particular case of mediatisation. This already existed when, for instance, radio stations had to pay license fees to mediatise music. But with digital ecosystems, such practises are widespread and continuously expanding. This in turn, makes internalisation – copyright exploitation – an iterative process adapting to new media, new practises, requiring new contracts and new pricing schemes.

The last post of this series examines economic issues and policy implications related to media ecosystems.